Scottish filmmaker Ruby Grierson blazed a trail through the 1930s with blistering socialist documentaries and innovative techniques. Yet, when her career was cut short by her early death, she was written out of film history, virtually forgotten for decades. 80 years after her death, Rachel Pronger examines Grierson’s remarkable life and legacy.

Eighty years ago, a ship travelling from Liverpool to Canada was struck by a torpedo and sank. In 1940, as war engulfed Europe, such horrors were not unusual, but this particular tragedy stood out. 258 passengers and crew were killed, including 77 child evacuees who had been on their way to supposed safety. Among the dead was 36-year-old filmmaker Ruby Grierson.

In her lifetime, Grierson was a star. As part of the British Documentary Film Movement she pioneered a new kind of filmmaking in the 1930s. She captured working-class lives on screen with unprecedented honesty, innovating techniques which would be crucial to development of documentary as we recognise it today. Her brother John was also a filmmaker, the founder of the movement in which his sister worked. While the two Griersons sometimes collaborated, their conflicting ideas led to clashes. Decades later, only one sibling would be widely remembered.

Today John Grierson is widely regarded as the father of documentary, a name familiar to film students around the world. For decades, Ruby’s work was virtually forgotten, barely mentioned in histories of the genre. Her contribution has been largely erased and it is only thanks to the work of feminist researchers that she is finally beginning to be credited for her contribution.

Ruby Grierson was born in 1904 in Stirling, Scotland. Her formidable mother, Jane Anthony, was a suffragette and Labour activist who raised eight children to be politically engaged and socially liberal. Ruby followed John to attend Glasgow University before training as a teacher, but a few years later she switched paths to move into filmmaking. In this apparently abrupt change of direction, Ruby was following once again in the footsteps of her older brother.

John’s journey into filmmaking began in the 1920s. While living briefly in the US, John had become immersed in film, working as a critic and writing extensively about an emerging genre he referred to as “documentary.” He was fascinated by the work of early documentarists such as Robert Flaherty, who shot from life to build gripping narratives about the lives of real people. These films were highly staged, but John was less interested in capturing reality than in the forms potential to illuminate social issues. On his return to London, he poured his ideas into his directorial debut. Drifters combined a shot-from-life narrative – a humble portrait of North Sea fishermen – with powerful cinematic techniques taken from Soviet Cinema, such as montage. Premiering in 1929, Drifters caused an immediate stir. John was heralded as the figurehead for a new kind of aesthetically daring, socially conscious non-fiction filmmaking. John seized the moment to assemble a network of eager, left-leaning young directors (the likes of Edgar Anstey, Arthur Elton and Paul Rotha) who became the hub of a new movement.

While the British Documentary Movement was officially led by John, their output was produced collectively. Directors, editors and writers worked collaboratively on each other’s projects, swapping roles and sharing ideas, united by the principle of a politically committed, progressive kind of filmmaking. The ‘Documentary Boys’ were infamous for their nightly pub gatherings, where they would drink, smoke and share ideas. So far, so 1930s Film Bros. Look closer however, through the plumes of pipe smoke, and you can spot women in their ranks.

In fact, the birth of the movement coincided with a brief golden age for women in British cinema. In the period leading up to and during the War, as state-sponsored filmmaking boomed and men were diverted into wartime occupations, the door to the Boy’s Club was left temporarily ajar. Women in film at this time had typically been relegated to administrative jobs, but now a small number of tenacious outliers seized the moment and became directors. The likes of Budge Cooper, Jill Craigie and Kay Mander, all went on to play important roles in the development of the British documentary. Among these trailblazers were Ruby, and her younger sister Marion, both of whom carved successful careers in the 1930s. The Grierson family became an unlikely dynasty.

Ruby began her career in 1935 working as an assistant on Housing Problems, an expose of urban slums. A campaign film that takes a matter-of-fact look at a social problem, Housing Problems is in many ways typical of the period, notably in its use of a clipped patrician voiceover and somewhat overbearing commentary. What makes the film remarkable, however, is its use of to-camera interviews, which allow residents to describe their experiences with little mediation. “This house is getting on my nerves,” declares the formidable Mrs Hill in one such interview, standing hand on hips before her crooked staircase, adding, “the upstairs is coming downstairs and it’s sinking… dirty filthy walls and the vermin in the walls is wicked.” Elsewhere, another woman, standing before peeling wallpaper, remembers waking up to find a rat on her head, while a quietly dignified father describes losing two children to the damp. This focus on working class people addressing the camera directly, in their own homes, lends a powerful intimacy that feels anachronistically modern. Although she worked uncredited, first-hand accounts attribute this innovation to Ruby Grierson. “The camera is yours,” she is reported to have said to her subjects, “now tell the bastards exactly what it’s like to live in the slums.” Although now a mainstay of documentary, this use of direct address was revelatory in the mid-1930s. For the first time, real people were seen to speak to the audience, in their own words, without the visible intervention of the filmmaker.

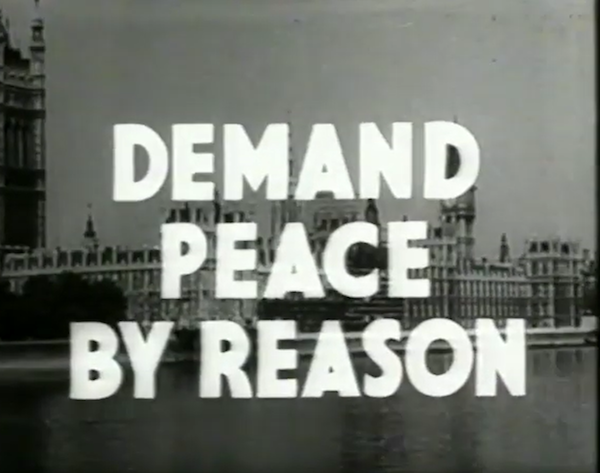

After Housing Problems, Grierson began to work as a director under her own name, building a reputation as a passionate filmmaker driven by a conviction that film could usher in a better world. As early as 1936, she was hitting headlines for co-directing People of Britain, a peace plea deemed so extreme in inter-war Britain that it was briefly censored until public outcry caused the ban to be overturned. Ruby’s influence can be felt again in the use of interviews which are presented unmediated by voiceover. “When there’s a quarrel between two people the police are sent to settle it,” observes one woman, crouched on a doorstep over a washboard and looking up briefly from her laundry to address the camera. “Why can’t a dispute between two nations be settled by the League of Nations?” People of Britain takes an emotive approach, breaking up this first-person testimony with emphatic intertitles and provocative imagery. A still of heavy artillery is displayed beneath the words “Money for Arms” while a voiceover declares, “Two thousand million pounds a year spent on arms.” Other intertitles incite the audience explicitly to “Demand Peace,” boldly underlining that controversial pacifist message. One particular image – the words “Make This a Symbol of Peace” written across a Union Jack – conjures a potent anti-colonialist sentiment which still resonates radically today.

Ruby’s approach to form was as bold as her choice of subject matter. As her career progressed, she honed other techniques that were to have a lasting influence. In 1938, she made two short films, The Zoo and You and Animals on Guard, which played powerfully with the dynamics between viewer and subject. Shot at London Zoo, the films offered a portrait of life in captivity with the focus as much on the human visitors as the zoo’s inhabitants. Director Richard Leacock served as an assistant on the project and remembered Ruby’s playful attitude, encouraging her team to crawl into the cages to shoot from the point of view of the animals. While the London Zoo films are now sadly lost, their influence lives on, most notably in the formative role they played in the development of Leacock as a filmmaker. He would go on to become a founding father of direct cinema, and traced a line back to Ruby, who he remembered as an open and original thinker. At a time when most documentaries maintained strict divisions between subject, spectator and filmmaker, Grierson was dissolving those boundaries, disappearing into the work to allow the audience to feel like an unseen observer, eavesdropping on the action. By seeking looser, less artificial ways to present the world, Ruby took the first steps towards the fly-on-the-wall perspective that has become a mainstay of the modern documentary.

Her role in developing these techniques demonstrate how Grierson’s filmmaking diverged from that of her peers. She openly clashed with her brother, motivated partly by her disapproval of some of his ideas. “The trouble with you is that you look at things as though they were through a goldfish bowl,” John recounted Ruby saying in one confrontation, “I propose to smash your goldfish bowl.” This clash captures a fundamental difference between the siblings. Although he was celebrated as the figurehead of the Documentary Movement, as John’s career progressed he was drawn more towards propaganda and advertising. While Ruby worked on propaganda in her career – a condition of work in state-subsidised filmmaking during the war years – these projects remained informed by her commitment to illustrating the reality of real people’s lives.

Ruby’s distinctive approach to even the most blatant propaganda commission is demonstrated by one of her last completed films. Made in 1940, They Also Serve centres on the quiet heroism of a working-class housewife as she holds her family together during wartime, and the story is told from the perspective of its protagonist. Ruby depicts with empathy the physical and emotional labour enacted by her heroine across a typical day – from picking vegetables, to comforting neighbours, to giving her husband a backrub. The voiceover, an endless list of chores and worries, allows us to hear her thoughts relayed in first person, itself an unusual choice of subjectivity. Thanks to Grierson’s low-key style, They Also Serve makes the viewer feel part of the family depicted, a relatable story of working-class struggle – which just happens to contain a government-approved message.

Shortly after finishing They Also Serve, Grierson was offered an assignment directing a film about evacuees. Her unobtrusive style, talent with people and teaching background made her a natural choice for the role. In 1940, the SS City of Benares set off for Canada with 400 souls on board. Among them were 90 children and Ruby, who was planning to document the children’s safe resettlement in the New World. It wasn’t to be. Ruby Grierson was lost at sea.

Grierson’s early death was noted in a smattering of hastily written obituaries, but already, the mechanics of forgetting were rolling into motion. Many of the articles noting her death identified Ruby foremost as “John’s filmmaking sister,” with little comment on her own work. When her films are discussed, titles, dates and facts are often wrong. Her death was sad but not unusual in the tragic churn of wartime. Years passed, the war ended, and Ruby Grierson became just another ghost.

John Grierson remained a prominent figure until his death in 1972. Passing references in John’s letters demonstrate that he never forgot his sister, yet is nevertheless implicated in Ruby’s historical erasure. From 1946’s Grierson on Documentary onwards, John collaborated with his friend and critic Forsyth Hardy, on a series of books which together were to constitute the official history of the British Documentary Movement. Hardy hero-worshipped his subject, and between them they constructed a simplified heroic narrative, the story of a single maverick male visionary leading his Documentary Boys into a bold new era. While John Grierson had been a supportive employer of women, neither he nor Hardy felt the need to acknowledge the vital role they had played in the movement. As a result, the official history that John and Hardy built erases the contributions not only of key women such as Cooper, Craigie and Mander, but also of John’s own wife Margaret Taylor (editor of Drifters) and his sisters.

This brazenly exclusionary history-making obscured Ruby’s story for decades. In 1994, Fiona Adams began to dig into Ruby’s history, producing a short documentary for BBC Scotland about her life. Reshooting History puts forward a compelling argument for Ruby Grierson’s legacy as a filmmaker, recounting her life and featuring interviews with prominent admirers, including documentarians Molly Dineen and Roger Graef. Graef is an especially passionate advocate, tracing her influence on his own work, Richard Leacock’s, and that of the Maysles brothers, firmly arguing for her reinstatement into the canon:

It was Ruby Grierson not John Grierson who started us all off… Her films, in paying attention to the detail and the truth and dignity of ordinary people’s lives, are what verité filmmaking has been built on.

Reshooting History also, brilliantly, includes memories from some of Ruby’s surviving peers, such as Leacock and Marion Grierson. By capturing this first-hand testimony, Adams preserves vital, soon to be lost oral history, a crucial intervention when so much female film work has historically been uncredited or minimised in official records.

Since the 1990s, as feminist perspectives have slowly become integrated into film courses and the issue of exclusionary film histories have begun to be confronted more directly, awareness of Ruby’s work in academia has gradually increased. Stub mentions of Ruby in key reference works, such as those written by Sylvia Paskin and Annette Kuhn and Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, have helped keep her name in circulation, but it has taken decades for more detail to emerge. Within the past five years, researchers like Sarah Neely and Isabel Segui have worked directly with the John Grierson Archive in Stirling to unearth, catalogue and make available documents, photographs and films that bring new life to Ruby’s story. Ruby and her fellow female documentarians have also become a focus at the BFI Archive, where restoration projects are underway that will make their work more widely available. Nonetheless, this process of recovery has been painfully slow.

Through Invisible Women, a feminist collective dedicated to screening female-directed work from the film archives, myself and co-founder Camilla Baier have screened Ruby Grierson’s work many times. The process of reshaping the film canon to reflect the achievements of women is long, exhausting and collaborative. In our work, we build on the many writers, researchers and curators who have discovered Ruby before us.

Female filmmakers are continually being remembered and forgotten, lost and re-discovered. This is why celebrating Ruby Grierson’s life and legacy is important on an individual level, but also on a collective one. Her story demonstrates, through a single prism, the shared struggle faced by women across film history. This is a struggle that continues through their lives and after their deaths: to be credited, to be recognised, to be remembered. Until we reckon with this erasure of our female filmmaking past, we will be unable to build an equitable future. 80 years on, let’s hope that this time, for Ruby, it sticks.

Rachel Pronger (@rachelpronger) is a writer, programmer and producer. She is cofounder of Invisible Women (@IW_Archives), an archive activist film collective which reinserts women into the history of cinema. Born in Bradford, she is currently based in Berlin.